Showing posts from category: International Relations

The Brazilian Empire of the Braganzas: Endgame Emperor, Dom Pedro II’s Rule

Pedro II’s reign as emperor of Brazil started in the least propitious of circumstances. The first and immediate threat to the longevity of his rule was that he was only five-years-old when he acceded, necessitating a regency in Brazil until he came of age to rule in his own right. The other obstacle was that Brazil was still a fledgling empire wracked by political instability. Civil wars and factionalism plagued the empire, a vast region posing extremely formidable challenges to rule … between 1831 and 1848 there were more than 20 minor revolts including a Muslim slave insurrection and seven major ones (some of these were by secessionist movements). Pedro II had more success in foreign policy, the empire expanded at the expense of neighbours Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay as the result of a series of continental wars. Some early historians saw Dom Pedro’s long reign in Brazil (1831-1889) as prosperous, enlightened and benevolent (he freed his own slaves in 1840) [Martin, Percy Alvin. “Causes of the Collapse of the Brazilian Empire.” The Hispanic American Historical Review 4, no. 1 (1921): 4-48. Accessed December 3, 2020. doi:10.2307/2506083.], certainly the emperor was viewed widely as a unifying force in Brazil for a good two-thirds of his reign.

1870s, on a course for turbulent waters in the empire From the 1870s onward however the consensus in favour of the rule of Pedro the ‘Unifier’ had started to show signs of fraying. The institutions that formed the three main pillars of the empire’s constitutional monarchical system—the landowning planter class, the Catholic clergy and the armed forces—were all becoming gradually disaffected from the regime, as were the new professional classes.

The landowning elite Pedro II’s reign came to an end in 1889 with his overthrow. The pretext for the removal of the Brazilian monarchy, according to the conventional thesis, was grievances of the planter oligarchy at the abolition of slavery (The Golden Law, 1888), which Dom Pedro had given his imprimatur to (CH Haring). This view holds that the landowners❋ deserted the monarchy for the republic because they were not compensated properly for their loss of slaves (Martin). This conclusion has been challenged by Graham et al on several grounds: the plantation owners dominated the imperial government of Pedro making them complicit in the decision to abolish slavery (ie, why would they be acting against their own interests?); many slave-owning planters favoured abolition because it brought an end to the mass flight of slave from properties; the succeeding republic government itself did not indemnify planters for their loss of slaves. More concerning than the abolition of slavery to the planters, in Graham’s view, was the introduction of land reform, something they were intent on avoiding at all costs. The planter oligarchs were willing to concede the end of the slave system so long as it forestalled land reform, the linchpin to real change in the society. Siding with the republicans, Graham concedes, was a calculated risk on their part, as there were many radical and reformist abolitionists¤ under the pro-republic umbrella with a very different agenda (national industrialisation) to them, but one they were willing to take⚉ [Hahner ; Graham, Richard. “Landowners and the Overthrow of the Empire.” Luso-Brazilian Review 7, no 2 (1970): 44-56. Accessed December 3, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3512758.]

🔺 Slaves on a fazenda (coffee farm), 1885

The clergy The conservative Catholic hierarchy were traditional backers of the emperor and the empire in Brazil. But a conflict of state in the 1870s between secularism and ultramontanism (emphasis on the strong central authority of the pope) undermined the relationship. This religious controversy involving the irmandades (brotherhood) drove a rift between the Brazilian clergy and the monarchy [Hahner, June E. “The Brazilian Armed Forces and the Overthrow of the Monarchy: Another Perspective.” The Americas 26, no. 2 (1969): 171-82. Accessed December 3, 2020. doi:10.2307/980297].

The national army The army had long-standing resentments about its treatment in Brazilian society…its low wages and the lack of a voice in the imperial cabinet were simmering grievances. Understandable then that together with the republicans, they were in the forefront of the coup against the monarchy, the pronunciamento (military revolt) that occurred in 1889. A key and popular figure influencing the younger officer element away from support for the monarchy was Manuel Deodoro da Fonseca (Marechal de campo in the army). Marshal Deodoro assumed the nominal leadership of the successful coup. Swept up in the turmoil of republican agitation, Deodoro, despite being a monarchist, found to his surprise that he had been elected the republic’s first president. The coup has been described as a “barrack room conspiracy” involving a fraction of the military whose “grievances (were) exploited by a small group of determined men bent on the establishment of the Republic” (Martin).

🔺 Allegory depicting Emperor Pedro’s farewell from Brazil (Image: Medium Cool)

🔺 Allegory depicting Emperor Pedro’s farewell from Brazil (Image: Medium Cool)

Revolution from above Historians have noted that the 1889 ‘revolution’ that toppled Pedro II was no popular revolution…it was “top-down”, elite-driven with the notable absence of participation from the povo (“the people”) in the process (Martin). In fact the emperor at the time still retained a high level of popularity among the masses who expressed no great enthusiasm to change the status quo of Brazil’s polity.

The Braganza monarchy, hardly a robust long-term bet With the health of the ageing Dom Pedro increasingly a matter of concern, the viability of Brazil’s monarchy came under scrutiny. For the military the emperor was not a good role model, Pedro’s own pacifist inclinations did not gel well with the army’s martial spirit. The issue of succession was also a vexed one…Princess Isabel who deputised several times when Dom Pedro was called away to Europe was thought of as a weak heir to the crown. She did not enjoy a positive public perception and Pedro’s transparent failure to exhibit confidence in her did little to bolster her standing, contributing to a further erosion of support for the monarchy [Eakin, M. (2002). Expanding the Boundaries of Imperial Brazil. Latin American Research Review, 37(3), 260-268. Retrieved December 3, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1512527]. The Brazilian monarchical state has been characterised as a kind of monarchy-lite which contributed to its lack of longevity – viz it failed to forge an hereditary aristocracy with political privileges, its titles mere honorifics not bestowing social privilege in Brazilian society. So that, by 1889, the empire had been reduced to a “hollow shell” ready to collapse (Martin).

A loose-knit empire? One perspective of the 19th century empire focuses on the sparseness and size of Brazil’s territorial expanse. Depreciating its status as an ‘empire’, this view depicts it as being in reality comprising something more like a “loose authority over a series of population clusters (stretching) from the mouth of the Amazon to the Río Grande do Sul” (Eakin). The lack of imperial unification, according to another view of the course of its history, surfaced as an ongoing struggle between the periphery (local politics) and the centre (national government), resulting in the weakening of the fabric of the polity [Judy Bieber, cited in Eakin].

Landless and disenfranchised Other issues in addition white-anted the legitimacy of Dom Pedro’s regime, notably the shrinking of the franchise. By 1881 the number of Brazilians eligible to vote had dropped alarmingly – less than 15% of what it had been just seven years earlier in 1874. And this trend was not corrected by the succeeding republic regime, portending a problematic future for Brazilian harmony because with the new republic came a rapid boost in immigration [‘The Old or First Republic, 1889-1930’, (Country Studies), www.countrystudies.us].

The cards in Brazil were always stacked in favour of the landed elite, an imbalance set in virtual perpetuity after the 1850 Land Law which restricted the number of Brazilians who could be landowners (condemning the vast majority to a sharecropper existence). The law concentrated land in fewer hands, ie, that of the planters, while creating a ready, surplus pool of labour for the plantations [Emília Viotti da Costa, The Brazilian Empire: Myths and Histories (2000)].

Structural seeds of the empire’s eclipse One theory locates Brazil’s imperial demise squarely in a failure to implement reform. The younger Pedro’s empire, projecting a rhetoric of liberalism which masked an anti-democratic nature, remained to the end unwilling to reform itself. The planter elite, with oligopolistic economic control and sway over the political sphere, maintained a rigid traditional structure of production—comprising latifúndios (large landholdings), slavery and the export of tropical productions (sugar, tobacco, coffee)—while stifling reform initiatives and opposing industrialisation [McCann, Frank D. The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, vol. 18, no. 3, 1988, pp. 576–578. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/203948. Accessed 3 Dec. 2020]. Another criticism of the monarchical government concerns its economic performance. Detractors point to the regime’s failure to take the opportunities afforded by the world boom in trade after 1880, a consequence of which was that powerful provincial interests opted for a federal system [‘The Brazilian Federal State in the Old Republic (1889-1930): Did Regime Change Make a Difference?’, (Joseph L. Love), Lemann Institute of Brazilian Studies, University of Illinois, www.avalon.utadeo.edu.co/]

Primeira República, “King Coffee” and industrial development

Initially the political ascendency in the First Republic lay with the urban-based military. However within a few years the government complexion was changed. The ‘Paulistas’, a São Paulo civilian cliche of landowners, elbowed the ineffectual Deodora aside. Exploiting differences between the army and the navy, the landowning elite then edged the remaining uniformed ministers out of the cabinet [Hahner], consolidating the “hegemonic leadership” of monolithic Paulista coffee planters in the republic✪.The First (or Old) Republic (1889-1930) was marked by uneven, stop-start spurts of industrialisation together with high level production of coffee for export. The Old Republic ended with another coup by a military junta in 1930 which in turn led to the Vargas dictatorship [Font; Graham].

Río de Janeiro, 1889 🔺

Endnote: The anomalous Brazilian empire of the 19th century During its 60-plus years of existence Brazil’s empire stood out among the post-colonial states of 19th century Central and South America as the single viable monarchy in a sea of republicanism. Briefly on two occasions it was joined by México, also a constitutional monarchy but one that didn’t truly take root. On the second occasion the fated Emperor Maximilian—who was Pedro II’s first cousin—tried to forge an imperial network of sorts with Brazil.

🔺 Confederados of Americana, Brazil (Photo: Business Insider)

🔺 Confederados of Americana, Brazil (Photo: Business Insider)

PostScript: Confederados in Brazil After the South’s defeat in the American Civil War, Pedro II, wanting to cultivate cotton in the empire, invited Southerners to settle in Brazil which still practiced slavery (others went to México or to other Latin American states, even to Egypt). Estimates of between 10 and 20 thousand took up Dom Pedro’s offer, settling mainly in São Paulo. Most of these Confederados found the hardships too challenging and returned home after Reconstruction, some however stayed on in Brazil with their descendants still living in places like the city in São Paulo named Americana [‘The Confederacy Made Its Last Stand in Brazil’, (Jesse Greenspan), History, upd. 22-Jun-2020, www.history.com].

⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯ ⎯

❋ a dominant force in Brazilian economics and society which had benefitted from the 1850 Brazilian land law which restricted the number of landowners

¤ such as Joaquim Nabuco

⚉ the planter elite decided in the end that a governo federal system would better protect their land monopolisation than the empire could (Graham)

✪ coffee from Minas Gerais, Río de Janeiro and especially São Paulo plantations were the mainstay of the Brazilian economy (Font)

The Brazilian Empire of the Braganzas: Founder-Emperor, Dom Pedro I’s Rule

Brazil at the start of the 19th century was the jewel in the imperial crown of Portugal, the kingdom’s largest and richest colony. In 1808 Napoleonic aggression had taken the European-wide war to the Iberian Peninsula. An inadvertent consequence of the invasion set Brazil on the path to independence. Portuguese prince regent, the future João VI (or John VI), not wanting to emulate the Spanish royals’ circumstance (incarcerated in a French Prison at Emperor Napoleon’s pleasure) fled Portugal for Brazil, reestablishing the Portuguese royal court in Río de Janeiro.

Dom Pedro o Libertador, an empire of his own

João returned to Lisbon as king of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves on the wave of the Liberal ‘Revolution’ (1820), leaving son Pedro as regent to rule Brazil in his stead. Unfortunately for him Pedro had his own plans, defying his father and the Portuguese motherland, he split Brazil off from Portugal. In a famous “I am staying” speech (Dia do Pico), Pedro rebuffed the demands of the Cortes (parliament) in Lisbon that he yield. Pedro’s timing was good, his move won the backing of the Brazilian landed class. [‘Pedro I and Pedro II‘, (Brazil: Five Centuries of Change), www.library.brown.edu]. Militarily, he met only limited resistance from Portuguese loyalists to his revolt. Aided by skilful leadership of the Brazilian fleet by ace navy admiral, the Scot mercenary Lord (Thomas) Cochrane, Pedro triumphed over his opponents with a relatively small amount of bloodshed, declaring himself emperor of Brazil in late 1822 and receiving the title of “Perpetual-Defender of Brazil”.

(Source: Bibliothèque National)

Pedro, despite benefiting from the able chief-ministership of José Bonifácio, soon found his imperial state on a rocky footing, embroiled in a local war with the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. In the conflict, Brazil’s southern Cisplatine province, encouraged by the Argentines, broke away from the empire, eventually re-forming as the independent republic of Uruguay (both Brazil and Argentina during this period harboured designs on the territory of Uruguay). On João VI’s death in 1826 Pedro I became king of both Portugal and Brazil, but immediately abdicated the Portuguese throne in favour of his daughter Maria II [‘Biography of Dom Pedro I, First Emperor of Brazil’, (Christopher Minster), ThoughtCo., Upd.15-May-2019, www.thoughtco.com]

Politics within the ruling House of Braganza in this time were turbulent, both in Portugal and Brazil. The king’s younger brother Miguel (“o Usurpador”) usurped the throne of the under-aged Maria, causing Pedro I to also abdicate the Brazilian throne and return to Europe to try to restore the crown to his daughter Maria. Pedro’s five-year-old son, Pedro II, succeeded him in a minority as the new emperor of Brazil in 1831. In Portugal Dom Pedro gathered an army and engaged in what was effectively a civil war between liberals and conservatives who were seeking a return to the rule of absolutism. The war spread into Spain merging into the larger First Carlist War, a war of succession to determine who would assume the Spanish throne. The Portuguese conflict was decided in favour of Dom Pedro and the liberals, but not long after in 1834 Pedro I died of TB.

A whiff of Lusophobia in the Brazilian air

Pedro I’s abdication of the Brazilian throne provoked a brief outbreak of Lusophobia (hatred of the Portuguese) in Brazil. Triggered by perceptions that Lisbon harboured designs to restore Brazil by force to its colonial empire, some Brazilians in a frenzy randomly attacked Portuguese property and killed a number of Portuguese-born residents [‘In the Shadow of Independence: Portugal, Brazil, and Their Mutual Influence after the End of Empire (late 1820s-early 1840s’, (Gabriel Paquette), e-Journal of Portuguese History, versão On-line ISSN 1645-6432, vol.11, no. 2 Porto 2013].

Retribution, Incapacitation, Deterrence, Rehabilitation? The French Carceral Presence in Colonial Africa and Indochina

France’s 19th century colonial empire (sometimes called the “second French colonial empire”) properly dates from the French invasion and eventual conquest of Algeria, 1830-47) [‘French Colonial Empires’, The Latin Library, www.thelatinlibrary.com]. Following the failed 1848 Revolution—the Parisian uprising having been quashed by General Cavaignac—just 468 political prisoners were transported to Algeria, an initial, modest number which grew exponentially after Louis-Napoleon’s 1851 palace coup. Thousands of dissidents ended up detained in prisons and forts in Algeria’s and Bône (Annaba) [Sylvie Thénault. Algeria: On the Margins of French Punitive Space?. 2015. HAL Id: hal-02356523 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02356523] Translator: Christopher Mobley, web.colonialvoyages.org].

(Credit: ‘The Algerian Story’)

Bagnes d’Afrique◇

The system in French colonial Algeria worked thus: the worst politicals were kept in confinement, the rest were despatched to depot camps, these were disciplinary’ camps where the convicts were consigned to terracing and irrigation projects, building ports, fortifications and roads, working in mines and quarries, or to colony camps which were mobile building sites – mainly assigned to rural areas, notably to clear land. Convicts were subjected to “hard labour at exhausting pace in a naturally trying environment”※. Convicts singled out for punishment in the Algerian penal system were not treated with lenience. Violence perpetrated against them included ingeniously devilish variations on the infliction of pain and rigid constraint in confined spaces (Thénault).

Deportation, Algeria to Guyane and Nouvelle Calédonie Residents of the colony committing offences against the law in French Algeria (which applied the same penal code as in Metropolitan France), could and were sentenced to relégation (exile) to other colonies in the empire⍟. A number of the convicted in Algeria ended up in French Guiana and New Caledonia, sentenced to harsh work regimes. Some deportés to Cayenne (Guiana) who escaped penal servitude there, found their way back to Algeria and a resumption of their outlaw activism. This contrasted with New Caledonia where some of the Algerian exiles were able to form ties with the Caldoche, especially the transported Communards, and settle permanently in New Caledonia after serving their terms (Thénault).

The three-way movement of convicted insurrectionists—from metropole to colony, from colony to metropole, and from colony to colony—was part of a deliberate policy by France. It’s purpose was to move insurgents “from environments where they were troublesome and render them useful somewhere else”⍉ (see also PostScript). As Delnore notes, within several years, as needs changed, deportation “became formalised and largely unidirectional”. With not enough free settlers from the parent country willing to live in Algeria, increasing the deportees from France obviously numerically enhanced the overall French presence in the colony while providing cheap labour [Delnore, Allyson Jaye. “Empire by Example?: Deportees in France and Algeria and the Re-Making of a Modern Empire, 1846–1854.” French Politics, Culture & Society 33, no. 1 (2015): 33-54. Accessed November 9, 2020. http://jstor.org/stable/26378216].

The Indochine ‘bastille’ The French republic established and consolidated its colonial hold over the land of ‘Vietnam’ (then comprising three sectors, Tonkin – northern Vietnam, Annam – central Vietnam and Cochinchina (southern Vietnam, Cambodia), and gradually established a penitentiary system. In the south this included the Côn Dào islands (near Saigon), also known as the Poulo Condor(e) islands, a prison colony from 1862 to 1975. The first Con Dao prison (Phu Hai) on Con Son island was built in 1862 to house both political dissidents from Vietnam and Cambodia. Plantations and quarries were set up to utilise the labour of the growing prison population. According to Peter Zinoman, almost all senior Vietnamese communist leaders except Ho Chi Minh spent time in one of the Con Dao pénitentiaires. Corruption and opium addiction was rampant within the prison staff and inmates. The Con Dao prison colonies were taken over by the South Vietnamese government in 1954 and closed in 1975 after the communist victory [‘Con Dao: Vietnam’s Prison Paradise’, (Peter Ford), The Diplomat, 08-Mar-2018, web.thediplomat.com].

The most famous French prison in the northern section of the country (Tonkin) was Hỏ Lò penal colony in Hanoi (commonly translated as “fiery furnace” or “Hell’s hole”), the French called it La Maison Centrale. It was built in the 1880s to hold Vietnamese political prisoners opposing the French colonists. During the Vietnam War, with tables turned, it was used to incarcerate American POWs who sarcastically referred to it as the “Hanoi Hilton”. Today it is a museum dedicated to the Vietnamese revolutionaries who were held in its cells, complete with an old French guillotine (the American section is a more sanitised part of the memorial bereft of any references to torture) [‘Inside the Hanoi Hilton, North Vietnam’s Torture Chamber For American POWs’, (Hannah McKennett), ATI, 08-Oct-2019, www.allthatsinteresting.com].

In the Annam (central highlands) part of Indochina, the Buon Ma Thuot penitentiary was yet another of the French colonialists’ special jails with a “hell on earth” reputation, built for Vietnamese political prisoners. Buon Ma Thuot was located in a remote, hard-to-access area encircled by near-impenetrable jungle and inflicted with malarial water. The penal colony was also seen as something of a training school for Vietnamese patriots, many of the revolutionaries who took part in the August Revolution (1945) in Dak Lak against the French were at one time incarcerated here [‘Buon Ma Thuot Prison’, http:en.skydoor.net/].

Punitive over the disciplinary approach The prison system in Indochine française did not “deploy disciplinary practices (such as the installation of) cellular and panoptic architecture”. Prisoners were housed in “undifferentiated⊞, overcrowded and unlit communal rooms”. “Disciplinary power” (in the Foucauldian sense) was not implemented in the Indochinese prisons…the coercion and mandatory labour dealt out was not aimed at rehabilitating or modifying or reforming the behaviour or character of inmates. Zinoman accounts for the discrepancy as an inability of colonial prison practice to adopt the prescribed theory of modern, metropolitan prison technologies at the time…this applied to French Indochina as equally it did to French Guiana (blight of bad record-keeping, incompetence management, personnel indiscipline/corruption), but he evidences other factors peculiar to Indochina – the persistence of local pre-colonial carceral traditions, the legacy of imperial conquest and the effects of colonial racism (“yellow criminality”) [Peter Zinoman, The Colonial Bastille: A History of Imprisonment in Vietnam 1862-1940, (2001)].

Endnote: Deportation v Transportation? These two terms in relation to penal colonies tend to be used interchangeably. In regard to France, after 1854 the authorities made a semantic distinction between common law prisoners who were described as being ‘transported’ (the term borrowed from the British carceral usage), and political prisoners who were said to be ‘deported’ – in some cases to the same colonies (Delnore).

(‘Prisoners Exercising’ VW Van Gogh)

PostScript:Theory applied to the French imperial colony French lawmakers and penologists in the 19th century tended to juggle two distinct but related rationales or approaches to the practice of deportation. One view, the penal colony as terre salvatrice (lit: “saving land”), held that deportation, having removed criminals from the “corrupting environment”, would through the discipline of hard work have a redemptive and healthy effect on them and permit their reintegration into French society. The second saw transportation to the overseas penitentiaire as the means for extracting the criminal element out of the ‘civilised’ society of the metropole, “separating France’s troublemakers from the rest of the population” (Delnore).

◂▸◂▸◂▸◂▸◂▸◂▸◂▸◂▸◂▸◂▸◂▸◂▸◂▸◂▸◂▸◂▸◂▸◂▸◂▸◂▸◂▸◂▸◂▸◂▸

◇ Algeria was the main African country where French penitentiaries were established but not the only one. France had other, smaller penal colonies on the continent, such as in Obock (in modern Djibouti) and in Gabon

※ other convicts were assigned to individual settlers and entrepreneurs to work mainly on private farms

⍟ some Muslim Algerians convicted in the colony were also sent to southern France and held under “administrative internment” – in part under the belief that incarcerating them in a Christian country might have a greater punitive impact on these criminals (Thénault)

⍉ there were French precedents for this – in 1800 Napoleon I deported Jacobin opponents to the Seychelles, and around the same time removed Black mutineers from French colonies in the West Indies and imprisoned them in mainland France and on Corsica (Delnore)

⊞ where both the accused and the convicted prisoners are indiscriminately detained together

⍒⍋⍒ ⍋

French Guiana and Devil’s Island – Bagne le plus diabolique

France’s penal colony network in New Caledonia (see preceding post) was not exactly a summer camp for delinquents, it was a brutal, unforgiving and unrelenting environment for existing rather than living. Comparatively though, it pales into lesser significant when stacked up against the unimaginable inferno of its South American equivalent in the colonies pénitentiaires of French Guiana (Guyane française).

The Napoleonic manoeuvre In 1851 Napoleon’s nephew Louis-Napoleon, elected president of the French Republic, staged a coup from above. With army backing he neutralised the national parliament and enacted a new constitution giving himself sweeping new dictatorial powers, a hefty step on the road to emulating his uncle by declaring himself emperor, Napoleon III, in 1852. With France’s jails and hulks overflowing with the incarcerated multitudes, swollen further by the emperor’s defeated opponents, much of the surplus prison population was transported to France’s Algerian colony. At the same time Louis-Napoleon took the opportunity to establish a new penal colony in French Guiana and send out the first lot of transportés. Transportation to penal colonies, especially to Guyane, to New Caledonia and to Algeria, allowed France to rid itself of dangerous and incorrigible offenders at home, and to punish them for their sins by subjecting them to a life of hard labour❋ [Jean-Lucien Sanchez. ‘The French Empire, 1542–1976’. Clare Anderson. A Global History of Convicts and Penal Colonies , Bloomsbury, 2018. hal-01813392.HAL Id: hal-01813392].

Economies of labour Aside from cleansing France of the criminal element, transportation served another purpose for Napoleon III. Slavery had been the engine of growth for France’s colonial empire, but France’s abolition of the institution in 1848 resulted in a massive shortage of cheap labour. Turning French Guiana (FG) and other French colonies into penitentiaries—replacing the lost plantation workers, the freed black African slaves (known as Maroons) with convicts in FG—neatly solved the problem [‘France’s “dry guillotine” a hell on earth for convicts’, (Marea Donnelly), Daily Telegraph, 22-Aug-2018, www.dailytelegraph.com.au].

Bagne le plus diabolique The penal system in Guyane française revolved around two principal locations⧆, one was the Prison of Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni which functioned as the destination of first arrival for transportés (and usually only a temporary home for the majority). From here, the worst of the bagnards (convicts), the recaptured escapees and the relégués (recidivists), were relocated down the coast to the other Guyane penitentiary, Bagne de Cayenne. Here, a small group of off-shore islands, Îles du Salut (Salvation Islands) comprised the penal colony on which French Guiana’s dark reputation hangs. Better known as Devil’s Island, a collective descriptor for three distinct islands, the farthest away and most inaccessible of which, Île du Diable, was reserved for a select group of prisoners⦿.

(Image: www.thevintagenews.com)

The history of Devil’s Island is one of notoriety and longevity (operating from 1852 to 1946). Conditions for inmates were horrendous… hard labour from six in the morning to six at night (including being assigned to endlessly building roads that were never intended to be finished); working and living in a malarial coast and tropical jungle environment; susceptibility to a host of diseases including yellow fever, typhus, cholera and malaria; the more dangerous prisoners solitarily confined to tiny cells 1.8m x 2m indefinitely, and often exposed to the elements [‘French Guiana Prison That Inspired “Papillon”, (Karin-Marijke Vis), Atlas Obscura, 11-Aug-2015, www.atlasobscura.com].

Île du Diablo (Photo: Romain Veillon / www.thespaces.com)

A tropical death camp A sense of mortality in the penal colony was ever-present – convicts fought and murdered each other, punishment by execution (by guillotine) was regularly meted out❂. For those who could no longer stand the psychological and physical torture of incarceration in such a sub-human hell hole, driven to near-insanity, the urge to escape (“Chercher la belle”) exerted a powerful pull. This however was virtually a suicidal course of action as would-be escapees faced shark-infested waters and jungles teeming with jaguars, snakes and other deadly beasts [‘The story of the world’s most infamous penal system – ever?’, (Robert Walsh), History is Now Magazine, www.historyisnowmagazine.com]. In the first 14 years of the Guyane prisons’ operation, two-thirds of the convicts perished (Sanchez) At its worst point Devil’s Island had a 75% death-rate.

The sentencing regime was particularly harsh…bagnards transported to FG were subjected to the penalty of ‘doubleage’. This meant that on the expiration of a prisoner’s sentence, he or she✦ had to remain working in the colony for an additional period that was equivalent to the original sentence. And if prisoners were sentenced to terms of more than eight years, this automatically became a life sentence (Donnelly).

⌂ the Dreyfus Tower

Dreyfus Affair puts the spotlight on Devil’s Island Among the over 52,000 déportés sent to Devil’s Island/Cayenne from its inception to 1936, its most famous inmate was Alfred Dreyfus, who had been wrongful arrested on a trumped-up charge of selling military secrets to Germany. Dreyfus endured over fours years on solitary Île du Diable before his case became a cause célèbre taken up by prominent citizens like novelist Emile Zola. Protests forced the French government—in a convoluted set of developments—to reopen Dreyfus’ case, retry him, re-convict him then free him and eventually exonerate him. The Dreyfus affair exposed entrenched anti-Semitism in the French military and in society [‘Devil’s Island Prison History and Facts’, Prison History, www.prisonhistory.net/].

⌂ the Devil’s Island story became widely known after ex-inmate Henri Charriere’s published account of his escape, ‘Papillon’, was made into a Hollywood movie in the early 70s

An anachronism of incarceration history The penitentiaries at Cayenne and Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni persisted for an inordinately long time, considering that apart from absorbing the overflow from the prison system in Metropolitan France they didn’t achieve all that much that was positive. The penal colonies were not only a humanitarian catastrophe, but an economic disaster…the planted crops failed badly and self-sufficiently was never achieved, signalling a complete failure in the objective of transforming the bagnards into settlers. In one year alone, 1865, the soaring cost of the FG enterprise reached in excess of 3.75 million francs! (Sanchez). After Salvation Army adjutant Charles Péan exposed the horrors, the utter inhumanity, of France’s Devil’s Island in a damning investigation⌽, the French authorities dragged their feet for another 25 years before they finally drew the curtain on this shameful chapter of their penal history [‘Devil’s Island’, Wikipedia, http://en.m.wikipedia.org].

(Map: BBC News)

Endnote: These days France calls Guyane française an overseas department rather than a colony, and the colonial prisons are barely a distant memory. Instead today FP hosts the Guiana Space Centre (close to the town of Kourou), a Spaceport run in conjunction with the European Space Agency.

Changing pattern of deportations from metropole to colonies 1852-1866: majority of deportees sent to French Guiana From 1866: deportees from Europe sent to New Caledonia From 1866: deportees from North Africa, Asia and the Caribbean sent to French Guiana

§§a rider to the system was that the ultimate destination of deportees could also depend on whether they were common or political prisoners

▂▂ ▂ ▂ ▂ ▂ ▂ ▂ ▂ ▂ ▂.▂ ▂ ▂ ▂▂

❋ while lightening the burden on the government for domestic prison expenditure

⧆ plus a scattering of sub-camps of convicts located around different parts of French Guiana

⦿ mainly traitors (or accused ones like Dreyfus) and political dissidents. In WWI it housed spies and deserters (Donnelly). Others falling foul of French colonial justice ended up in Caribbean penal holdings on islands such as Guadalupe and Martinique

❂ the macabre pet name of inmates for Devil’s Island was the “Dry Guillotine” (“it kills it’s victims more slowly than the actual guillotine but kills them just as certainly”)

✦ women convicts were transported to FG, but there were only just shy of 400 deported in the duration of the penal colony

⌽ in 1928 duty of care was still non-existent: the prison administrators’ gross negligence was still resulting in 400 inmates dying each year and 2,400 freed prisoners left to fend for themselves

Australian Anxieties about the Neighbourhood: 19th Century French New Caledonia, an Uncomfortable Presence in a “British Lake”

These days the Australian government it seems welcomes the French presence in New Caledonia. Canberra offered a tacit endorsement of France’s retention of its colonial hold over New Caledonia following the recent referendum which voted for a second time against independence for the French Pacific colony. From a geopolitical standpoint it seems that it is in Canberra’s interest for the French, a Western naval power, to continue to have a stake in the Pacific…as it constitutes the existence of a “significant counterweight” to the uncertain but fluid intentions of China in respect of the western Pacific [‘Australia is part of a Black region; it should recognise Kanaky ambition in New Caledonia’, (Hamish McDonald), The Guardian, 25-Oct-2020, www.theguardian.com].

Noumea, NC ▵

Noumea, NC ▵

A look back into history reveals that Australia hasn’t always been as sanguine about the French settlement in its near Pacific island neighbour. The French connection with New Caledonia formally began in 1853 when it established a colony, settling a small expat population from Metropolitan France. Prior to this time the British through its colony in New South Wales had assumed a sort of “titular control” of New Caledonia❋. As well as being within the British-Australian sphere of influence, there was a pre-existing triangular trade between Australia, the New Caledonian islands and China… Australian merchants traded iron and metal utensils and tools and tobacco for sandalwood with the native (Kanak) population, which the merchants then exchanged with China for tea [‘The Perils of Proximity: The Geopolitical Underpinnings of Australia’s View of New Caledonia In The 19th Century’, (Elizabeth Rechniewski), Portal. 2015. Vol 12, No 1. http://doi.org/10.5130/portal.V12i1.4095].

France’s decision to annex New Caledonia (NC)—a further sign to the British of French imperial designs in the south Pacific after its earlier acquisition of Tahiti—prompted a considerable degree of commotion within the Australian colonies. They criticised the colonial office in London for being lax in not having secured the colonisation of NC by Britain to block just such a takeover by the French. Australian newspapers like the Moreton Bay Courier had been warning for some time of NC’s suitability as an ideal location for a naval station from which to attack the Australian coast (Rechiewski).

Pacific pénitentaires◌◌◌◌ ◌◌◌◌Australian concerns and anxieties grew exponentially in 1864 when the French turned NC into a penal colony using Britain’s penal system as a model – prisons were established at two locations, at Île Nou (Noumea Bay) on Grande Terre (NC’s main island), and a second pénitentaire on Île des Pins (Isle of Pines, or Kunié in Melanesian culture)✪. The outcry from the press in Australia and from some politicians against the French presence intensified…a NSW colonial secretary urged Britain take diplomatic action to discourage Paris from continuing the transportation of “these scum of France”. The intensity of Australian hostility to the NC penal colony, has led one historian to suggest that the fierceness of the opposition may have reflected an element of post-convict shame” within Australian society itself, given that transportation to Australia had only recently been ended [Jill Donohoo, ‘Australian Reactions to the French Penal Colony in New Caledonia’, Explorations: A Journal of French-Australian Connections, 54, 25-45, www.isfar.org.au].

▿ Isle of Pines: vestiges du Bagne (Photo: Marco Ramerini/www.colonialvoyage.com)

19th century “boat people”: Apprehensive eyes looking west ◌◌◌◌ ◌◌◌◌◌◌◌ ◌◌ ◌◌◌◌ In the last quarter of the century the principal external anxiety, especially for Queenslanders and New South Welshmen, was the fear of ‘invasion’ from bagnards or forçats (convicts) in NC. Many east coasters on the mainland were fixated on the threat of convicts—either having escaped from the NC colony or whose sentences had expired or had been pardoned—coming to Australia. Although perhaps exaggerated in actual numbers involved, the incidence of arrivals was more than merely perception, with periodic if isolated boatloads landing mainly on the Queensland coast (also in NSW and some reached New Zealand). With France flagging its intent to increase its transportation of habitual criminals to NC in the 1880s, anxieties further intensified. An additional concern was that in the event of a war erupting between France and Britain, France might unleash boatloads of the most dangereux kind of convicts in menacing numbers onto coastal Australian towns. A French proposal at the time to up the annual transportation numbers of bagnards including lifers to NC and to extend transportation to the adjoining Loyalty Islands as well, did nothing to abate Australian apprehensions [‘The problem of French escapees from New Caledonia’, (Clem Llewellyn Lack), Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, Vol. 5, No. 3, 1954].

Queensland’s northward anxieties◌◌◌◌◌ ◌◌◌◌◌ ◌◌At the same time the Queensland colonial government in particular was equally anxious about imperial German ambitions in the region. Fear of German intentions to annex the eastern half of New Guinea to its immediate north, prompted Queensland first to push the colonial office in London to ratify a British protectorate over the southern portion of eastern New Guinea, and then to unilaterally and rashly plunge ahead with its own plans for annexation in 1883 [‘Queensland’s Annexation of Papua: A Background to Anglo-German Friction’, (Peter Overlack), Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, Vol. 10, No. 4, 1979].

Conditions in the Île des Pins were of an extreme nature, the bagnards were subjected to cellular isolation, material deprivation and endemic disease, and worse, they were brutalised, beaten and tortured by the guards. The severity of their treatment was conceivably aggravated by the invidious situation of the wardens who themselves were in a kind of “occupational neverworld” (Toth). Entrapped in a low pay, no future work environment, the guards were looked on by both administrators and prisoners as merely “loathed turnkeys” [‘The Lords of Discipline. The Penal Colony Guards of New Caledonia and Guyana’, (Stephen A Toth). Crime, Histoire and Sociétés. Vol. 7. No. 2, 2003. Varia. http://doi.org/10.4000/che.544].

By the time France ceased transportation to the Nouvelle Calédonia pénitentaires in 1897—a decision prompted by the economic failure of using bagnard labour to colonise NC rather than by any humanitarian motives—anywhere up to a total of 40,000 convicts had been transported since 1864. This included some 5,000 political prisoners – the Communards, transported for their involvement in the Paris Commune revolt at the end of Napoleon III’s disastrous 1870 war with Prussia (Lack).

Spying for the nation, the first tentative steps ◌◌◌◌◌◌◌◌◌◌◌◌◌◌◌◌◌◌◌◌◌ Nouvelle Calédonia and other Pacific islands played a role in the formative days of Australia’s espionage history. In 1902 Major William Bridges, acting on orders from the commander of the Australian land forces General Hutton, undertook a military spy mission to NC with the purpose of ascertaining the strength of fortifications in the French Pacific colony. Bridges came to this task already with experience of intelligence work having been on a mission to Samoa in 1896 to suss out German designs for the island [‘The growth of the Australian intelligence community and the Anglo-American connection’, (Christopher Andrew), Intelligence and National Security, Vol. 4, 1989 – Issue 2, 218-256, http://doi.org/10.1080/02684528908431996; Richard Hall, The Secret State: Australia’s Spy Industry, (1978)].

Aside from having French and German ambitions in the region to worry about, the Australian colonies from the 1890s had a new threat to preoccupy them, Japan. Through a series of bold and aggressive moves—annexing Formosa (Taiwan) and Korea , establishing a foothold on the Chinese mainland, and in defeating Tsarist Russia in a Pacific war—Japan signalled it’s arrival as a force in the Asia/Pacific region, and a rival to British-Australian (or Australasian) dominance in the western Pacific. As the 20th century progressed Australian anxieties about the “Japanese menace” would reach a level of hysteria.

PostScript: New Hebrides – contested ground ◌◌◌◌◌ ◌◌By the 1880s the Australian colonies’ concern about the French in NC had extended to elsewhere in Oceania, especially its ambitions for nearby New Hebrides (NH). Some in Australia feared that France might use NC as a base to annex Nouvelles-Hebrides and energies in Australia were directed at ensuring the British government blocked any French attempts to plant the French tricolour on the island group. In 1886 France did just this, establishing military posts with small detachments of troops at two ports, Havannah and Sandwich. The Queensland government, alarmed that this presaged French intentions to also use NH as a convict dump, pressured London into securing assurances from Paris to the contrary (Lack).

Condominium compromise Notwithstanding this, the French maintained a presence in NH and tensions between the British and French on the islands persisted, including some violent exchanges between the two groups. In 1904-06 a curious solution of sorts was reached with an accord in which both sides made concessions⚉, future governance of NH was to comprise an Anglo-French Condominium. This created a dual system with separate administrations (known as residencies) in Port Vila, police forces, prisons and hospitals▣. The French and British residencies had control over their own ressortissants (‘nationals’) with separate Francophone and Anglophone communities – which led to the inevitable communication difficulties. All of this administrative duplication proved unwieldy and at times unworkable. In the middle of what some cynics tagged “the Pandemonium” rather than the Condominium were the disadvantaged indigenous population of NH, the Ni-Vanuatu who were left stateless (proving difficulties for some of them later trying to travel overseas when they found that they lacked a proper passport) [‘New Hebrides’, Wikipedia, http://en.m.wikipedia.org; Lack]. The unique if bothersome governance arrangement continued until 1980 when the island state finally gained independence as Vanuatu.

↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜↝↜

❋ the island chain’s first visit from a European was by Captain Cook in 1774 who gave it its name but didn’t formally claim if for Great Britain

✪ prior to colonising New Caledonia France had shown an interest in the southwestern region of Australia as a possible repository to offload criminals from overcrowded French jails [Bennett, B. (2006). In the Shadows: The Spy in Australian Literary and Cultural History. Antipodes, 20(1), 28-37. Retrieved November 2, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org./stable/41957504]. A few French convicts were despatched to a spot in the Pacific even more remote, Tahiti

⚉ France recognised the British occupation of Egypt in return for recognition of its interests in Morocco

▣ though there was a Joint Court established for all residents

Germania, Mega-City Stillborn: Hitler’s Utopian Architectural Dream

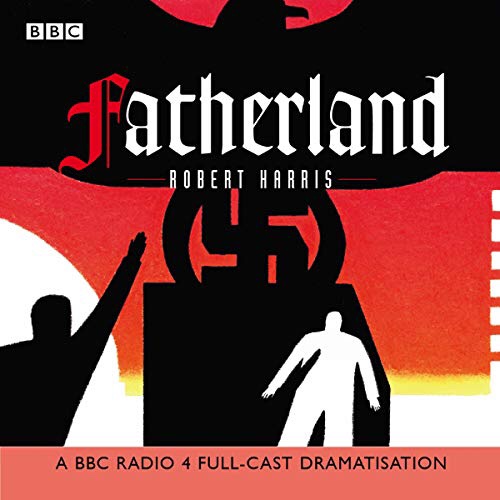

In Robert Harris’ speculative novel Fatherland—a “what if”/alternative view of postwar European history set in 1964—Adolf Hitler is very much alive, having won the Second World War. Through his “Greater German Reich” the Führer rules an empire stretching from “the Low Countries to the Urals” with Britain reduced to a not-very-significant client state. In the novel’s counterfactual narrative Hitler’s architect Albert Speer has completed part of Hitler’s grand building project for Berlin – including the 120m high “Triumphal Arch” and the “Great Hall of the Reich” (the “largest building in the world”). We know that none of the above scenario came to fruition, but we do know from history that part of Hitler’s plans post-victory (if he won) was to radically transform the shape and appearance of his capital city Berlin.

In Robert Harris’ speculative novel Fatherland—a “what if”/alternative view of postwar European history set in 1964—Adolf Hitler is very much alive, having won the Second World War. Through his “Greater German Reich” the Führer rules an empire stretching from “the Low Countries to the Urals” with Britain reduced to a not-very-significant client state. In the novel’s counterfactual narrative Hitler’s architect Albert Speer has completed part of Hitler’s grand building project for Berlin – including the 120m high “Triumphal Arch” and the “Great Hall of the Reich” (the “largest building in the world”). We know that none of the above scenario came to fruition, but we do know from history that part of Hitler’s plans post-victory (if he won) was to radically transform the shape and appearance of his capital city Berlin.

Weltreich or Europareich?

Under a future German empire, Berlin, to be known as Germania※, would be the showcase capital. Historians are divided over whether the Nazis’ ultimate goal was global dominance (Weltherrschaft)—in which case Germania would be Hitler’s Welthauptstadt (‘world capital’)—or was more limited in its objective, intent on creating a European-wide reich only (as posited by AJP Taylor et al). Either way, Hitler’s imperial capital was to be built on a monumental scale and grandeur which reflected the “1,000-Year Reich” and its stellar story of military conquests and expansion – in effect a theatrical showcase for the regime [‘Story of cities #22: how Hitler’s plans for Germania would have torn Berlin apart’, (Kate Connolly), The Guardian, 14-Apr-2016, www.theguardian.com].

Weltreich or Europareich?

Under a future German empire, Berlin, to be known as Germania※, would be the showcase capital. Historians are divided over whether the Nazis’ ultimate goal was global dominance (Weltherrschaft)—in which case Germania would be Hitler’s Welthauptstadt (‘world capital’)—or was more limited in its objective, intent on creating a European-wide reich only (as posited by AJP Taylor et al). Either way, Hitler’s imperial capital was to be built on a monumental scale and grandeur which reflected the “1,000-Year Reich” and its stellar story of military conquests and expansion – in effect a theatrical showcase for the regime [‘Story of cities #22: how Hitler’s plans for Germania would have torn Berlin apart’, (Kate Connolly), The Guardian, 14-Apr-2016, www.theguardian.com].

Nazi utopia Showing off Germania to the world for the Führer was all about one-upping the capitalist West. Immense buildings symbolising the strength and power of Nazism convey a message of intimidation, a declaration that Hitler’s Germany could match and exceed the great metropolises like New York, Paris and London. Accordingly, the Hamburg suspension bridge had to be on a grander scale than its model in San Francisco, the constructed East-West Axis in Berlin had to outdo the massive Avenida 9 de Julio in Buenos Aires [Thies, Jochen, ‘Hitler’s European Building Programme’, Journal of Contemporary History, July 1, 1978, http://doi.org/10.1177/002200947801300301].

Hitler & Speer: (Source: www.mirror.co.uk)

The architect/dictator Hitler put Speer in charge of the massive project but always fancying himself as having the sensibility of an architect, Hitler retained a deep interest in its progress✪. Rejecting all forms of modernism▣ Hitler’s architectural preferences were rooted in the past – “Rome was his historical model and neoclassical architecture was his guiding aesthetic” [Meng, M. (2013). Central European History. 46 (3), 672-674. Retrieved October 24, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/43280636]. The Germania building projects writ on a gargantuan scale, were an unmistakable statement, a means for the dictatorship “to secure (its) place in history and immortalise (itself) and (its) ideas through (its) architecture [Colin Philpott, Relics of the Reich: The Buildings the Nazis Left Behind, (2016)].

(Source: http://the-man-in-the-high-castle.fandom.com/wiki/)

On the Germania drawing board Taking pride of place, the architectural centrepiece of the Germania blueprint, was the Volkshalle (‘People’s Hall)✦, a staggeringly large edifice inspired by the Pantheon in Rome—a dome 290m high and 250m in diameter—which had it been completed would have been the largest enclosed space on Earth, capable of holding up to 180,000 people. Linking with the Volkshalle via an underground passageway similar to a Roman cryptoporticus was to be the palace of Hitler (Führerpalast). The monolithic domed People’s Hall would have dwarfed and obscured the close-by, existing structures, the Reichstag and the Brandenburg Gate.

Among a host of other uncompleted buildings in Germania was the Triumphal Arch (Trumpfbogen)…at over 100m high three times the size of the iconic arch in Paris it was modelled on. Hitler’s utopian Berlin metropolis was scheduled for completion in 1950, the onset of war however delayed construction which then ceased for good after the Wehrmacht suffered serious setbacks on the Russian Front in 1943 [‘Hitler’s World: The Post War Plan’, (Documentary, UKTV/SBS, 2020]. The Nazis planned thousands of kilometres of networks of motorways spanning the expanding empire (linking Germania with the Kremlin, Calais to Warsaw, Klagenfurt to Trondheim, etc). These too remained unrealised under the Third Reich (Thies). Another project reduced to a pipe dream was the Prachtallee (Avenue of Splendours), a north-south boulevard which was intended to bisect the East-West Axis.

Model of ‘Germania’

Costing Germania The projected cost of all the regime’s building projects has been estimated at in excess of 100 billion Reichsmarks (Thies). But for the Nazis, how to bankroll a building venture of such Brobdingnagian proportions, was not a major concern. Their reasoning was that once victory was attained, the conquered nations would provide all of the labour and materials necessary for the construction projects (Connolly).

A slave-built Germania German historian Jochen Thies’ pioneering study, Hitler’s Plans for World Domination: Nazi Architecture and Ultimate War Aims’ (English translation 2012), argues that as well as reintroducing the architectural solutions of antiquity for its mega-city, the Nazi elite sought to replicate “the society and economy of that time, i.e. a slave-owning society”, as the basis for Hitler’s “fantasy world capital” (Thies). For a venture of such scale the program firstly needed ein großer Raum (a large space), requiring thousands of ordinary Germans, both Jews and Gentile, to be forcibly evicted from their homes which were then bulldozed✮. Concentration camps were established deliberately close to granite and marble quarries to facilitate the building projects…in proximity to Berlin, the Nazis used Jewish prisoners at Sachsenhausen concentration camp (Oranienburg) for the slave and forced labour force⌖ [‘Inside Germania: Hitler’s massive Nazi utopia that never came to be’, Urban Planning’, (Chris Weller), Business Insider, 24-Dec-2015, www.businessinsider.com].

Germania – a Nazi utopia to see but a nightmarish dystopia to live in The plan if it had been realised would have seen huge swathes of the city torn down to make way for the mega-construction mania. With a multiplicity of ring-roads, tunnels and autobahns, Germania would have been pedestrian-unfriendly, lacking in amenities for city-dwellers, sterile, not green (outside of the grand stadium there was no parks or major transit lines)…a city almost completely bereft of human dimension – what was once an attractive living space would have disappeared under the Third Reich’s urban planning imperatives (Roger Moorhouse in Weller).

Nuremberg: Macht des dritten Reiches (Source: The Art Newspaper)

Of course Berlin wasn’t the only city in the German Reich singled out to get an extreme physical makeover. Four other cities were also awarded special Führer City Status and earmarked for the same grandiose Nazi treatment – Linz (where Hitler grew up), Hamburg, Munich and Nuremberg. The last city, made famous for holding the mass Nuremberg party rallies, its Zeppelin Field Grandstand, now a racetrack, had a capacity for up to 150,000 party faithfuls.

Endnote: A neo-German city on the Vistula The newly acquired lands of the empire were also subjected to the NSDAP urban transformation template. Warsaw was to be rebuilt as a new German city (the Pabst Plan⊞) – a living space for a select number of ‘Ayran’ Germans, while its more numerous, “non-Ayran” Polish residents were to be shepherded into a camp across the River Vistula, a separate but handily located slave labour force for the ‘renewal’ (i.e. rebuild) of Warsaw…had the Pabst Plan proceeded historic Polish culture in the city would have been obliterated in the upheaval (‘Hitler’s World: The Post War Plan’).

⧾𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪𝄪⧾

※ ‘Germania’ was the name ascribed to the lands of the Germanic peoples in Ancient Roman times

✪ Hitler had always been intrinsically interested in architecture, back in his Linz days the failed artist had been advised to take up architecture instead

▣ the same applies to art, Hitler rejected the modern movements like Cubism, Surrealism and Dada, labelling them “degenerate art”

✦ also known as the Große Halle, the ‘great hall’

✮ leading to a housing crisis in Berlin, aggravated by some over-zealous officials who destroyed houses prematurely and unnecessarily, simply in the hope of earning the Führer’s approval (Thies)

⌖ as demands for labour intensified, the Nazis widened the pool of forced labour to include PoWs and anyone deemed deviant by the state, ie, beggars, itinerants, Gypsies, leftists, homosexuals (Connolly)

⊞ Pabst was the Nazis’ chief architect for Warsaw

(Image: www.timetoast.com)

(Image: www.timetoast.com)